A relationship between the Collatz conjecture and the Fibonacci numbers

Disclaimer 1

The findings presented in this article are not peer reviewed. They are

published here to gather some initial feedback. The findings should be

submitted to a journal in the coming weeks.

Disclaimer 2

The writing and the mathematical findings in the article were produced

without AI assistance. All mistakes are my own. If you have any

questions or suggestions, feel free to contact me.

Summary for a general audience

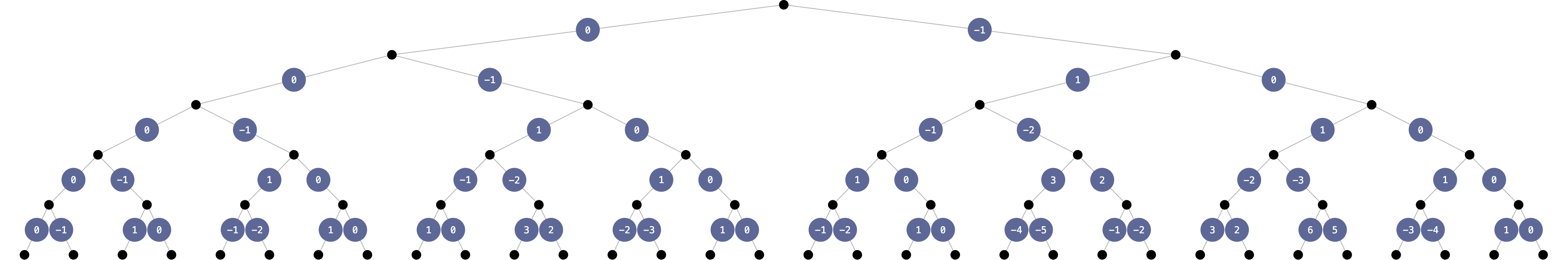

There is an infinite binary tree with integer edge labels that starts like this:

The labels can be defined recursively via the recurrence relation $$R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = R(x_1, \ldots, x_{k+1}) - x_0 R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k})$$ and $R(x_0) = -x_0$. The values $x_i$ take values in $\szo$ and determine the "path" through the tree. For example, $R(1, 0, 1) = -2$, because you start from the root and go "right, left, right", which leads you to an edge labeled $-2$.

The recurrence relation is somewhat similar to that of the signed Fibonacci numbers $F_n$, which start $-1, +1, -2, +3, -5, +8, \ldots$ and can be defined by $F_0 = -1, F_1 = +1$ and $F_{n+1} = F_{n-1} - F_{n}$. In fact, our tree $R$ contains the signed Fibonacci numbers. You can reach them by alternating between "right" and "left" turns in the tree. In other words, $R(1) = -1, R(1, 0) = +1, R(1,0,1)=-2, R(1,0,1,0)=+3$ and so on.

The tree is also directly related to the Collatz conjecture. Recall the Collatz map $$ C(n) = \begin{cases} \frac{n}{2} \; &\text{ if $n \equiv 0 \mod 2$ } \\ \frac{3n + 1}{2} \; &\text{ if $n \equiv 1 \mod 2$}. \end{cases} $$ The Collatz conjecture is the famous statement that if you start with a positive natural number $n$ as your value, and you keep applying $C$ to your value, you will eventually reach $1$. It is well known that it suffices to show that the values $C^k(n)$ eventually alternate between odd and even values. That is because an odd step followed by an even step corresponds to a computation $C(C(n)) = \frac{3n + 1}{4}$ which is strictly decreasing for $n > 1$.

It is also well known that the map $C$ can be extended to the $2$-adic integers. In this larger domain, we can observe any desired odd/even behaviour in iterations of $C$. For example, say you want to find a starting value $n$ which exhibits the following behaviour: $n$ is odd, $C(n)$ is odd, $C^2(n)$ is even, $C^3(n)$ is even, $C^4(n)$ is odd, $C^5(n)$ is odd, $C^6(n)$ is even... so we want to alternate between two "odds" and two "evens". In the $2$-adic integers, it is well-known that there is exactly one starting value $n$ that exhibits this behaviour.

That is where the connection to the tree $R$ takes place. You can step through the above infinite tree and start with two right turns, then two left turns, then two right turns again, always writing down the labels you find. They will start $-1,0,1,-2,2, \ldots$. Call these labels $r_0, r_1, \ldots$. Then the $2$-adic integer $n$ we are looking for will be given by $$ n = \sum_{i=0}^\infty 2^i r_i. $$

Coming back to the Fibonacci numbers, since we can alternate "right" and "left" in the tree to get the numbers $F_n$, this procedure should yield a value $n$ which, under the Collatz iteration, alternates between "odd" and "even". That value is clearly $n=1$. In other words, the findings imply the well-known formula $$ 1 = \sum_{i=0}^\infty 2^i F_{i}, $$ which is neat!

The point of this article is that the above tree links the Fibonacci numbers and the Collatz conjecture in a surprising way. The findings might open up an opportunity to study the Conjecture from a number theoretic perspective.

Introduction

In this article we consider the Collatz map of the form $$ C(n) = \begin{cases} \frac{n}{2} \; &\text{ if $n \equiv 0 \mod 2$ } \\ \frac{3n + 1}{2} \; &\text{ if $n \equiv 1 \mod 2$}, \end{cases} $$ defined on the 2-adic integers $\zp$. The Collatz-conjecture asserts that for positive natural numbers $n$, some iterate $C^k(n)$ equals $1$. It is well known that it suffices to show that the values $C^k(n)$ eventually alternate between odd and even values [1].

An important tool in the study of the Collatz conjecture is the conjugacy map $\phi$, first considered in 1985 [1] and extensively studied by Bernstein and Lagarias [2]. Its inverse $\phi^{-1}$ can be defined directly via $$ \phi^{-1}(n) := \sum_{k=0}^\infty (C^k(n) \mod 2) 2^k. $$ The function $\phi^{-1}$ thus encodes the parity of the iterates $C^k(n)$ as a 2-adic integer. It can be shown [2] that the Collatz conjecture is equivalent to $\phi^{-1}[ \N_+ ] \subseteq \frac{1}{3} \Z$.

The function $\phi$ maps a given 2-adic integer $x$, interpreted as an infinite stream of zeros and ones, to a 2-adic integer $\phi(x)$ whose behaviour under the Collatz iteration in terms of even/odd steps is precisely that stream. For example, the $2$-adic value $x = - \frac{1}{3}$ has 2-adic expansion $- \frac{1}{3} = (1,0,1,0,\ldots)_2$ and we have $\phi(- \frac{1}{3}) = 1$, because the value $1$ under the Collatz iteration alternates between odd and even steps.

Perhaps surprisingly, it can be shown [2] that the map $\phi$ satisfies an explicit formula given by $$ \phi(x) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty 2^k\frac{x_k}{3^{x_0 + \ldots + x_{k-1}}} $$ where $\sum_{k=0}^\infty 2^k x_k = x$ is the 2-adic expansion of $x$. This representation of $\phi$ involves an infinite sum of non-integer values.

In this article we prove the following representation of $\phi$ as an infinite sum of integers: $$ \phi(x) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty 2^k R_k(x), $$ where $$ R_k(x) = \sum_{i=0}^k x_i (-1)^{1 + k-i} {k-i+(x_0+\ldots+x_{k-1}) \choose k-i}. $$ The values $R_k(x)$ fulfill $R_0(x_0) = -x_0$ and the formula $$ R_{k+1}(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = R_{k}(x_1, \ldots, x_{k+1}) - x_0 R_{k}(x_0, \ldots, x_{k}). $$ The numbers $R_k$ can be seen as a natural generalization of the signed Fibonacci numbers, both because of the recurrence relation, and because they actually contain the signed Fibonacci numbers. Consider the alternating $x_0 = 1, x_1=0, x_2=1, \ldots$. With $F_k := R_{k}(x_0, \ldots, x_{k})$ we obtain $F_0=-1$ and the standard formula $F_{k+1} = F_{k-1} - F_{k}$ for the signed Fibonacci numbers $(F_k) = (-1, 1, -2, 3, -5, 8, \ldots)$. This also implies the well-known $2$-adic identity $1 = \sum_{i=0}^\infty 2^i F_{i}$. The numbers $R_k$ admit a natural visualization as an infinite binary tree with labeled edges, which we call $R$.

More generally, we show that in the $p$-adic integers ($p$ prime), the function defined by $H(n) = H_i(n)$ for $n \equiv i \mod p$ with $H_i$ of the form $H_i = \frac{n-i}{p} + a_i n + b_i$ admits an integer representation for the conjugacy map $\phi_H$, given by $\phi_H(x) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty 2^k R_k(x)$ where $R_0(x_0) = x_0 - pb_{x_0}$ and $$ R_{k+1}(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = R_{k}(x_1, \ldots, x_{k+1}) - a_{x_0} R_{k}(x_0, \ldots, x_{k}). $$

In the Collatz case, we have $a_0 = b_0 = 0$, $a_1 = b_1 = 1$ and $a_{x_0} = b_{x_0} = x_0$.

The article starts with some brief general findings on iterating functions in $\zp$. We then introduce the concept of tree representations of contracting functions in $\zp$. With the main theorem, we then show how to derive a tree representation with a recurrence relation as above. Finally, we consider the tree $R$ for the Collatz conjecture, and state some of its properties.

Parity maps

We work in the $p$-adic integers $\zp$ for $p$ prime, where there is a shift map $S$ given by $S(n):=\frac{n-(n \mod p)}{p}$ as defined in [2]. Consider any map $T\colon \zp \to \zp$. We define the parity map $\psi_T$ as $$ \psi_T(n) := \sum_{k=0}^\infty (T^k(n) \mod p) p^k. $$ The parity map encodes the parities that an iteration of $T$ produces. We find studying the parity map directly more fruitful than studying the conjugacy map studied in other articles [2].

In this article, we focus on the case where $T$ is in a certain sense linear. The properties of $T$ can be better understood by expressing it in one of two normal forms. In this chapter we focus on defining those normal forms and give some motivation for considering them. The proofs in this chapter are omitted as they are not difficult and are not necessary for the main result of this article.

The properties of the normal forms directly influence properties of $\psi_T$ as well as the novel formulas for $\psi_T^{-1}$, which we will show in the next chapter.

Definition

Given a map $T$ on $\zp$, its first normal form is the collection of

maps $T_0, \ldots, T_{p-1}$ on $\zp$ given by $$T_i(n) = T(np + i),$$ so that

for each $n\in \zp$ with $n \equiv i \mod p$, we have $T(n) =

T_i(\frac{n-i}{p})$.

The importance of the normal form is captured in the following Remark, where we remind the reader of the well-known fact that a distance-preserving map on $\zp$ is always surjective and thus an isometry.

Remark

Given a map $T$ on $\zp$, the following statements are equivalent:

- Each $T_i$ in the first normal form of $T$ is distance-preserving: $|T_i(n) - T_i(m)| = |n-m|$ for $n, m \in \zp$.

- $\psi_T$ is distance-preserving.

- $T$ is locally expanding in the following sense: For $n, m \in \zp$ with $n \equiv m \mod p$, we have $\abs{T(n)-T(m)} = p \abs{n-m}$.

Similarly, the following statements are equivalent:

- Each $T_i$ in the first normal form of $T$ is contracting: $|T_i(n) - T_i(m)| \leq |n-m|$ for $n, m \in \zp$.

- $\psi_T$ is contracting.

- For $n, m \in \zp$ with $n \equiv m \mod p$, we have $\abs{T(n)-T(m)} \leq p \abs{n-m}$.

□

Example

In the case of the Collatz map $T=C$, we have $C_0(n) = n$ and $C_1(n)=3n+2$,

both of which are clearly distance-preserving, so $\psi_C$ is an isometry.

In the next chapter, we see how the first normal form directly informs an explicit formula for the conjugacy map $\psi_T^{-1}$. The same is true for the second normal form:

Definition

Given a map $T$ on $\zp$, its second normal form is the collection of

maps $\hat{T}_0, \ldots, \hat{T}_{p-1}$ given by $\hat{T}_i(n) =

T(n)-\frac{n-i}{p}$, so that for each $n\in \zp$ with $n \equiv i \mod p$, we

have $T(n) = \hat{T}_i(n) + \frac{n-i}{p}$. Here $\hat{T}_i$ is defined on

$\{n \in \zp \mid n \equiv i\}$.

Remark

Given a map $T$ on $\zp$, the following are equivalent:

- Each $\hat{T}_i$ in the second normal form of $T$ is contracting.

- For each $T_i$ in the first normal form of $T$, the map $T_i$ is distance-preserving, and the map $T_i - \text{id}$ is strictly contracting: $|(T_i(n) - n) - (T_i(m) - m)| < |n-m|$ for $n, m \in \zp$ and $n \neq m$.

- The map $\psi_T$ is distance-preserving, and the map $\psi_T - \text{id}$ is strictly contracting.

Note that for $p=2$, if $T_i$ is distance-preserving, then $T_i - \text{id}$ is always strictly contracting. In $p=2$, we therefore see that $\hat{T}_i$ is contracting if and only if $T_i$ is distance-preserving.

As for the first normal form we can state everything for the case of $\hat{T}_i$ distance-preserving. The following are equivalent:

- Each $\hat{T}_i$ in the second normal form of $T$ is distance-preserving.

- For each $T_i$ in the first normal form of $T$, the map $T_i$ is distance-preserving, and the map $T_i - \text{id}$ is "exactly" contracting: $|(T_i(n) - n) - (T_i(m) - m)| = \frac{|n-m|}{p}$ for $n, m \in \zp$ and $n \neq m$.

- The map $\psi_T$ is distance-preserving, and the map $\psi_T - \text{id}$ is exactly contracting.

□

Example

In the case of the Collatz map $T=C$, we have $\hat{C}_0(n) = 0$ and

$\hat{C}_1(n)=n+1$, both of which are clearly distance-preserving, so $\psi_C$

is an isometry and $\psi_C - \text{id}$ is strictly contracting, which sounds

interesting at first, but can be trivially verified by hand.

Definition

A map $f$ on $\zp$ is called linear if it is of the form $f(n) = a n + b$ for

some $a, b \in \zp$. Note: Such a map is always contracting. It is

distance-preserving if and only if $a \not\equiv 0 \mod p$.

Remark

The map $\hat{T}_i$ in the second normal form of $T$ is linear if and only if

$T_i$ in the first normal form of $T$ is linear and the leading coefficient

$a_i$ fulfills $a_i \equiv 1 \mod p$.

In that case, if we have $T_i(n) = a_i n + b_i$, we have $\hat{T}_i(n) = (n - i) \frac{a_i - 1}{p} + b_i$.

□

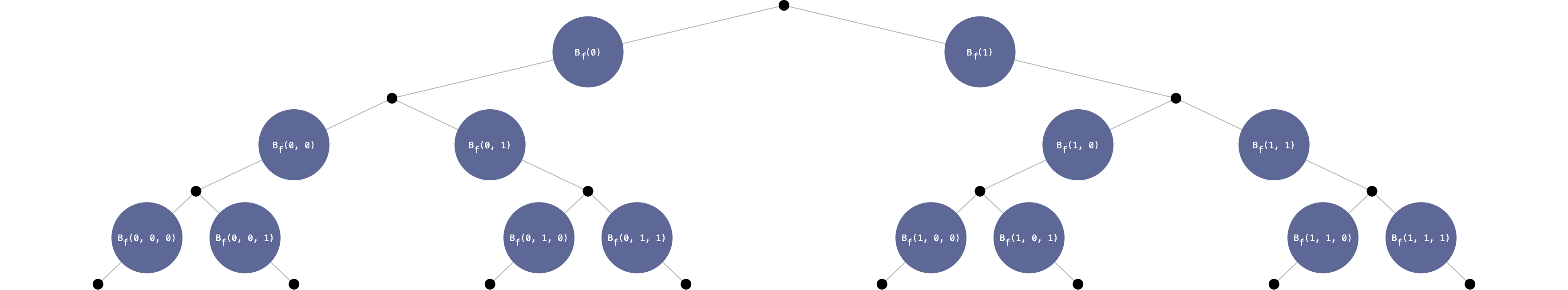

Tree representations

Any distance-preserving map is obviously contracting, and every contracting map has a convenient representation in form of a tree. Say $f$ is a contracting map on $\zp$ and consider two inputs $a, b \in \zp$. We call the coefficients in the base-$p$ expansion of $a, b$ their "bits". Since $f$ is contracting, it is clear that if $a$ and $b$ agree on the first $k$ bits, then $f(a)$ and $f(b)$ agree on their first $k$ bits (in fact, that is exactly much the definition of "contracting"). This means that the first $k$ bits of $f(a)$ only depend on the first $k$ bits of $a$. We can thus write $f$ as $$ f(a) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty R_f(x_0(a), \ldots, x_k(a)) p^k \\ \text{where } a = \sum_{k=0}^\infty x_k(a) p^k \text{ and } x_k \in [p]. $$ where $R_f$ is a function defined on $\tp := [p] \cup [p]^2 \cup [p]^3 \cup \ldots$ with domain $[p]$. We use the common shorthand $[p] := \{0, 1, \ldots, p-1\}$. The map $R_f$ can be visualized as an infinite tree where each node has $p$ children. The label of the node reached after taking through the tree the path $(x_0, \ldots, x_k)$ has label $R_f(x_0 \ldots, x_k)$:

We call maps from $\tp$ to $[p]$ exact trees on $\zp$. It is not hard to see that there is a one-to-one correspondence between contracting functions on $\zp$ and exact trees on $\zp$.

However, exact trees as defined above are often hard to express explicitly. We thus define general trees as follows:

Definition

A tree on $\zp$ is a map from $\tp := [p] \cup [p]^2 \cup [p]^3 \cup

\ldots$ to $\zp$ (note the codomain). It can be visualized as in the image

above.

Remark

Any tree gives rise to a contracting function: If $R$ is a tree on $\zp$, and

$a \in \zp$ with base-$p$-expansion $a = \sum_{k=0}^\infty x_k p^k$, then we

define $$ f_R(a) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty p^k R(x_0(a), \ldots, x_k(a)) $$ and this

is a contracting function. On the other hand, every contracting function has

infinitely many tree representations, exactly one of which is exact. A

contracting function is distance-preserving if and only if its exact tree $R$

is balanced, meaning that for any fixed $x_0 \ldots, x_{k-1}$ in $[p]$, the

set $$ \{R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k-1}, x_k) \mid x_k \in [p] \} $$ contains all

$[p]$ equivalences classes $\mod p$.

□

We now get to the main theorem of the article.

Theorem

Let $T$ be a map on $\zp$ whose second normal form is linear, so that for $n

\in \zp$, $i \in [p]$ and $n \equiv i \mod p$, we have $$ T(n) = a_i n + b_i +

\frac{n-i}{p} $$ for some $a_i, b_i \in \zp$.

Define the parity map as before via $\psi_T(n) := \sum_{k=0}^\infty (T^k(n) \mod p) p^k$.

Then the parity map is distance-preserving, and its inverse $\psi_T^{-1}$ has a tree representation $R \colon [p] \cup [p]^2 \cup [p]^3 \cup \ldots \to \mathbb{Z}$ given by $R(x_0) = x_0 - p b_{x_0}$ and the recursive formula $$ R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = R(x_1, \ldots, x_{k+1}) - a_{x_0} R(x_0, \ldots, x_k) $$

for $k \geq 1$.

In other words, for any infinite sequence $(x_k)$ with values in $[p]$, the value $n := \sum_{k=0}^\infty p^k R(x_0, \ldots, x_k)$ is the unique $p$-adic integer that fulfills $$ T^k(n) \equiv x_k \mod p. $$

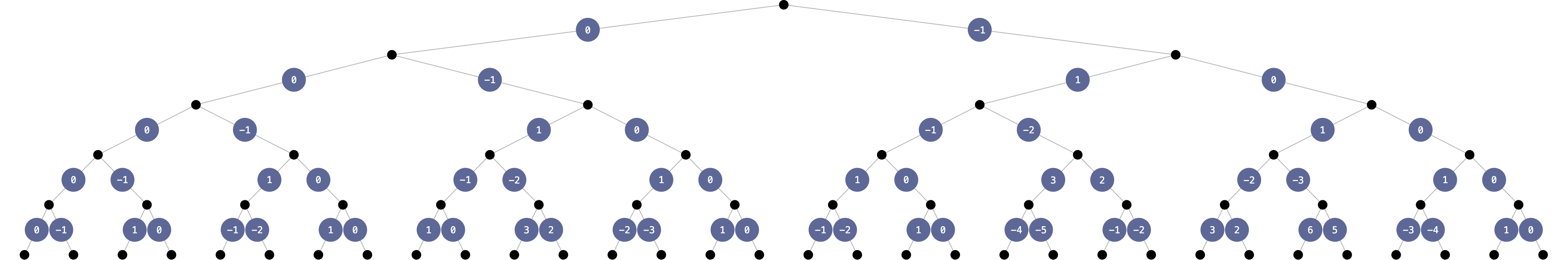

In the case of the Collatz map $T = C$, we have $p=2$ as well as $a_0 = b_0 = 0, a_1 = b_1 = 1$. The tree $R$ is thus given by $R(x_0) = -x_0$ and $R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = R(x_1, \ldots, x_{k+1}) - x_0 R(x_0, \ldots, x_k)$.

Proof

Why is $\psi_T$ distance-preserving? Take $n, m \in \zp$ with $n \neq m$ and

$\abs{n-m} = p^{-k}$. If $k > 0$, then $n \equiv m \equiv i \mod p$, for some

$i \in [p]$. Then $\abs{T(n) - T(m)} = \abs{(\hat{T}_i(n) - \hat{T}_i(m)) +

(S(n) - S(m))} = p^{-(k-1)}$ because $\hat{T}_i$ is contracting and can be

omitted. This procedure of applying $T$ can be continued to see that the

minimal $j \in \N_0$ with $T^j(n) \not\equiv T^j(m) \mod p$ is exactly $j =

k$. By definition of $\psi_T$, we thus have $\abs{n-m} =

\abs{\psi_T(n)-\psi_T(m)}$. Since $\psi_T$ is distance-preserving, it is

bijective and invertible.

Let $d \in \zp$ with base-$p$-expansion $d = \sum_{k=0}^\infty x_k p^k$. We want to show that $$ \psi_T^{-1}(d) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty p^k R(x_0, \ldots, x_k) $$ Set $n:=\psi_T^{-1}(d)$. We now define recursively a sequence of values $Q_k$ in the $p$-adic numbers (not just $p$-adic integers!): $$ Q_0 := \psi_T^{-1}(d) \\ Q_{k+1} := \frac{Q_k - R(x_0, \ldots, x_k)}{p}. $$ Note the following: If we can show that each $Q_k$ is in fact a $p$-adic integer, then we are done. This is because in that case, the sum $\sum Q_k p^k$ converges, and we can argue using telescoping as follows: $$ \sum_{k=0}^\infty p^k R(x_0, \ldots, x_k) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty p^k Q_k - \sum_{k=0}^\infty p^{k+1} Q_{k+1} = Q_0 = n = \psi_T^{-1}(d). $$ Because of this, we write $Q_k(n)$ and $x_k(n)$ for the values defined above. This is justified because these values depend on $d$ and therefore on $n$, since $d = \psi_T(n)$. Our goal is now to prove the following claim:

CLAIM 1: For all $n \in \zp$ and all $k \in \mathbb{N}_0$, we have $Q_k(n) \in \zp$.

Note that for any $n \in \zp$, we have $Q_0(n) = n \in \zp$, and also $a_{x_0(n)} \in \zp$. By a simple induction argument, it thus suffices to prove the following claim:

CLAIM 2: For all $n \in \zp$ and all $k \in \mathbb{N}_0$, we have $Q_{k+1}(n) = Q_k(T(n))-a_{x_0(n)} Q_k(n)$.

We now prove claim 2 by induction on $k$ and start with $k=0$. Note that by definition of the second normal form, we have $$ Q_0(T(n)) = T(n) = \frac{n - x_0(n)}{p} + \hat{T}_{x_0(n)}(n) = \frac{n - x_0(n)}{p} + a_{x_0(n)} n + b_{x_0(n)} $$ and thus $$ Q_0(T(n)) - a_{x_0(n)} Q_0(n) = \frac{n - x_0(n)}{p} + b_{x_0(n)} = \frac{n - (x_0(n) - p b_{x_0(n)})}{p} = \frac{n - R(x_0(n))}{p} = Q_1(n). $$ This settles the case $k=0$. Now we show the induction step $k \to k+1$.

After rearranging, we need to show $Q_{k+1}(T(n)) = Q_{k+2}(n)+a_{x_0(n)} Q_{k+1}(n)$. At this point, it is important to recall that the values $x_k(n)$ are defined as the base-$p$-expansion of $d = \psi_T(n)$. But $\psi_T$ is a parity map, so the base-$p$-expansion is simply $x_k(n) = (T^k(n) \mod p)$. In particular, we have $x_k(T(n)) = x_{k+1}(n)$. To finish up, by definition of $Q_{k+1}$, we have $$ p Q_{k+1}(T(n)) $$ $$ = Q_k(T(n)) - R(x_0(T(n)), \ldots, x_k(T(n))) \quad \text{(def. of $Q_{k+1}$)} $$ $$ = Q_{k+1}(n) + a_{x_0(n)} Q_k(n) - R(x_0(T(n)), \ldots, x_k(T(n))) \quad \text{(induction)} $$ $$ = Q_{k+1}(n) + a_{x_0(n)} Q_k(n) - R(x_1(n), \ldots, x_{k+1}(n)) \quad \text{(change $x_k$ arguments)} $$ $$ = Q_{k+1}(n) + a_{x_0(n)} Q_k(n) - R(x_0(n), \ldots, x_{k+1}(n)) - a_{x_0} R(x_0, \ldots, x_k) \quad \text{(recursive formula for $R$)} $$ $$ = p Q_{k+2}(n) + p a_{x_0(n)} Q_{k+1}(n). \quad \text{(def. of $Q_{k+2}, Q_{k+1}$)} $$

This proves the main theorem.

□

Remark

For completeness, we state a similar theorem based on the first normal form.

The proof works the same way, but is simpler. The resulting formula has long

been known for the case of the Collatz map; however, it might be less

interesting, because it results in non-integer values.

Let $T$ be a map on $\zp$ whose first normal form is linear, given by $T_i(n) = a_i n + b_i$ with $a_i \not\equiv 0 \mod p$. Then the parity map $\psi_T$ is invertible, and its inverse $\psi_T^{-1}$ has a tree representation $R \colon [p] \cup [p]^2 \cup [p]^3 \cup \ldots \to \mathbb{Z}$ given by $R(x_0) = x_0 - p \frac{b_{x_0}}{a_{x_0}}$ and the recursive formula $$ R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = \frac{1}{a_{x_0}} R(x_1, \ldots, x_{k+1}) $$

for $k \geq 1$. This implies the explicit formula $$ R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = \frac{ x_k a_{x_k} - p b_{x_k}}{\prod_{i=0}^{k-1}a_{x_i}}. $$

□

Investigating the Collatz case

We now take a closer look at the implications for the Collatz map $$ C(n) = \begin{cases} \frac{n}{2} \; &\text{ if $n \equiv 0 \mod 2$ } \\ \frac{3n + 1}{2} \; &\text{ if $n \equiv 1 \mod 2$}. \end{cases} $$ The tree $R$ is given by $R(x_0) = -x_0$ and $R(x_0, \ldots, x_{k+1}) = R(x_1, \ldots, x_{k+1}) - x_0 R(x_0, \ldots, x_k)$.

Using induction, one can prove the following explicit formula for $R$: $$ R(x_0, \ldots, x_k) = \sum_{i=0}^k x_i (-1)^{1 + k-i} {k-i+(x_0+\ldots+x_{k-1}) \choose k-i} = \sum_{i=0}^k x_{k-i} (-1)^{1 + i} {i+(x_0+\ldots+x_{k-i-1}) \choose i}. $$

The tree visualization begins as follows:

Remark

The tree $R$ has the following properties for any $x_0, \ldots, x_k \in \szo$:

- $R(0, x_0, \ldots, x_k) = R(x_0, \ldots, x_k)$. Visually, this is the self-similarity in the left half of the tree.

- $R(x_0, \ldots, x_k) = R(x_0, \ldots, 0) - x_k$.

- $R(1, x_0, \ldots, x_k) = (-1)^{k} + \sum_{i=0}^k (-1)^{k+i} R(x_0, \ldots, x_i)$.

- Assume $y_1, \ldots, y_j \in \{0\}$ are all zero. If $j$ is even, then $R(1, y_1, \ldots, y_j, x_0, \ldots, x_k) = R(1, x_0, \ldots, x_k)$. If $j$ is odd, then $R(1, y_1, \ldots, y_j, x_0, \ldots, x_k) = 2 (-1)^{k+1} + R(1, x_0, \ldots, x_k)$. Visually, this is the self-similarity in the left half of the right side tree.

Proof

(1.) This follows directly from the recursion formula. (2.) Follows directly

by induction. (3.) Induction on $k$. For $k=0$ we need to show $R(1, x_0) = 1

+ R(x_0) = 1 - x_0$ which can be verified by computation (or read from the

above visualization). For the induction step $k \to k+1$, we have by the

recursion formula: $$ R(1, x_0, \ldots, x_k, x_{k+1}) \\= R(x_0, \ldots, x_k,

x_{k+1}) - R(1, x_0, \ldots, x_k) \\= R(x_0, \ldots, x_k, x_{k+1}) +

(-1)^{k+1} - \sum_{i=0}^k (-1)^{k+i} R(x_0, \ldots, x_i) \\= (-1)^{k+1} +

\sum_{i=0}^{k+1} (-1)^{k+1+i} R(x_0, \ldots, x_i) $$ which is what we needed

to show. (4.) Assume first $j=1$. Set $z_0 := 0, z_i := x_{i-1}$ for $1 \leq i

\leq k+1$. Then we have (using (1.) and (3.) and $R(0) = 0$): $$ R(1, 0, x_0,

\ldots, x_k) \\= R(1, z_0, \ldots, z_{k+1}) \\= (-1)^{k+1} + \sum_{i=0}^{k+1}

(-1)^{k+1+i} R(z_0, \ldots, z_i) \\= (-1)^{k+1} + (-1)^{k+1} R(0) +

\sum_{i=1}^{k+1} (-1)^{k+1+i} R(z_1, \ldots, z_i) \\= (-1)^{k+1} +

\sum_{i=1}^{k+1} (-1)^{k+1+i} R(x_0, \ldots, x_{i-1}) \\= (-1)^{k+1} +

\sum_{i=0}^{k} (-1)^{k+i} R(x_0, \ldots, x_{i}) \\= (-1)^{k+1} + R(1, x_0,

\ldots, x_k) - (-1)^{k} \\= 2(-1)^{k+1} + R(1, x_0, \ldots, x_k). $$ This is

the effect of adding one zero at the beginning. Adding another one cancels

this out, since $2(-1)^{k+1} + 2(-1)^{k+2} = 0$.

□

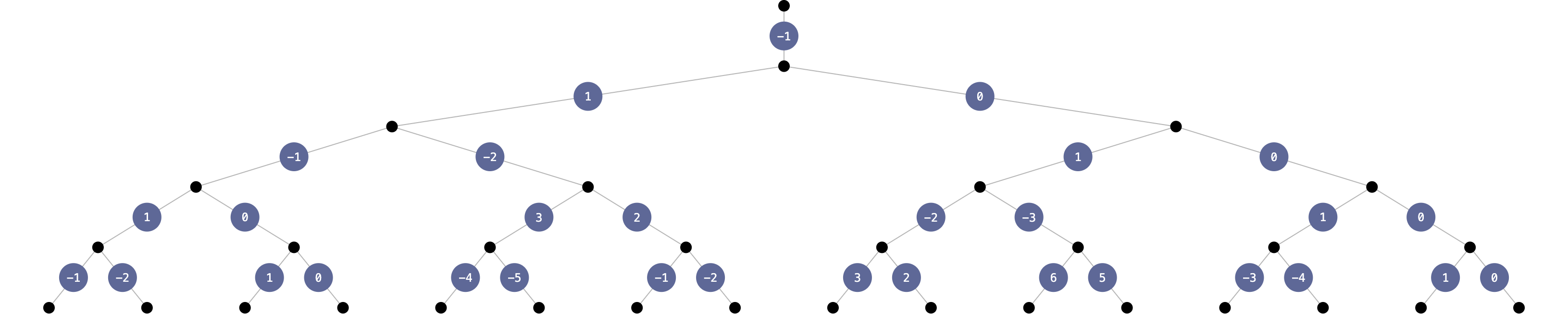

The first fact above means that leading zeros can be omitted, which strongly suggests an indexing scheme based on nonnegative integers. Indeed, for $n \in \N_0$ with base-$2$ expansion $n = \sum_{i=0}^k 2^i x_i$, where $x_i \in \szo$, we can define $$ r(n) := R(x_k, \ldots, x_0). $$ For example, $r(5) = r(101_2) = R(1, 0, 1) = -2$.

This is well defined because adding zeros at the end of the base-$2$ expansion of $n$ corresponds to adding zeros at the beginning of $R(x_k, \ldots, x_0)$, neither of which changes the value.

The sequence of integers $r(0), r(1), r(2), \ldots = R(0), R(1), R(1,0), \ldots$ starts with $0, -1, 1, 0, -1, -2, 1, 0, \ldots$

In this view, the entire left half of the visualization becomes obsolete. We can visualize the tree better by only showing values $R(x_0, \ldots, x_k)$ with $x_0 = 1$ (essentially the right side of the previous visualization):

The sequence $r$ just reads the edge labels row by row.

Remark

The previous properties can be stated in terms of the integer sequence $r$.

- We have $r(0) = 0, r(1) = -1$ and for $n \in \N_+$ the recursive formula $r(n) = r(n \mod 2^{\lfloor \log_2(n) \rfloor}) - r(\frac{n-(n \mod 2)}{2})$. The first summand removes the most significant bit, the second one removes the least significant bit (and shifts). This can also be stated as follows. For $n \in \N_+$ and $k > \lfloor \log_2(n) \rfloor$, we have $r(n) = r(n+2^k) + r(S(n+2^k))$, where $S$ is the shift function.

- Let $(x_k)$ be an infinite sequence of values in $\szo$. To find the unique $2$-adic integer $n$ whose odd/even step behaviour in step $k$ under the Collatz iteration is exactly $x_k$, proceed as follows. Define $a_0 := x_0$ and $a_{k+1} = 2 a_k + x_{k+1}$. Then $n = \sum_{k=0}^\infty 2^k r(a_k)$.

- If $n \in \N_0$ is even, then $r(n+1) = r(n) - 1$.

- $r(2^k) = (-1)^{k+1}$.

- Let $n \in \N_+$ and $k = 1 + \lfloor \log_2(n) \rfloor$. Then for all $j \in \N_0$, we have $r(n + 2^{k + j}) = (-1)^{k + (j \mod 2)} + \sum_{i=0}^k (-1)^{i} r(S^i(n))$, where $S$ is the shift function.

□

Further work

The findings in this article link the Fibonacci numbers and the Collatz conjecture in a surprising and hopefully interesting way. They might open up an opportunity to study the Conjecture from a number theoretic perspective.

In future articles, we will look at further properties of the tree $R$ and the corresponding integer sequence $r(n)$. We will also publish some more theoretical results about parity maps. A little teaser might be in order. While we so far have studied the parity map $\psi_C$ for the Collatz map $C$, one can show that $C$ itself is the parity map of another map $T$ - at least, except for the first output bit. More precisely is a map $T$ such that $S(C(n)) = S(\psi_T(n))$ for all $n \in \zp$, where $S$ is the shift function. This map $T$ can be described very explicitly.

References

- Lagarias, Jeffrey C. "The 3x + 1 Problem and Its Generalizations." The American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 92, no. 1, 1985, pp. 3-23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2322189

- Bernstein, D. J., and Lagarias, J. C. "The 3x + 1 Conjugacy Map." Canadian Journal of Mathematics, vol. 48, no. 6, 1996, pp. 1154-1169. https://doi.org/10.4153/CJM-1996-060-x

Feel free to email me at mail@vincentrolfs.dev. Or you can follow me on Mastodon at @vincentrolfs@hachyderm.io.